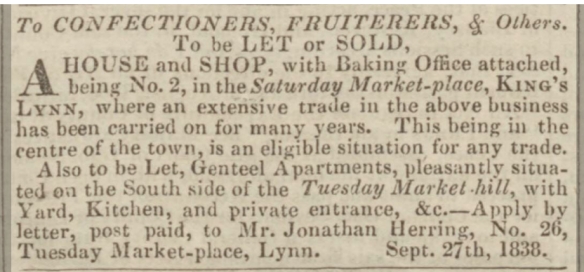

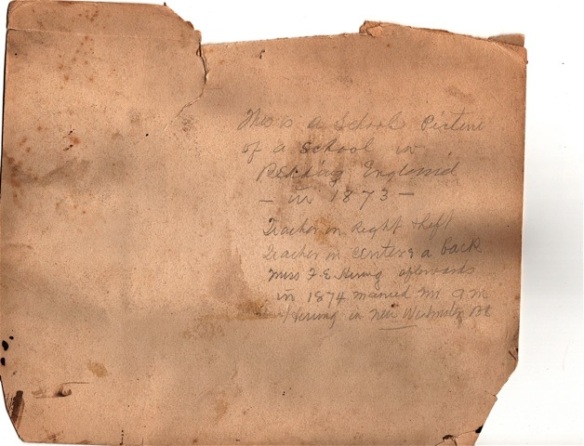

The earliest photo we have of Frances Elizabeth Herring is this group photo taken in 1873 with the description written on the reverse.

Frances Elizabeth Herring, teacher in Reading, England 1873

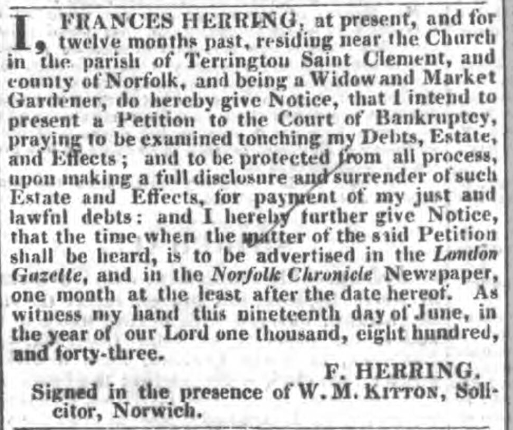

Back of Photo

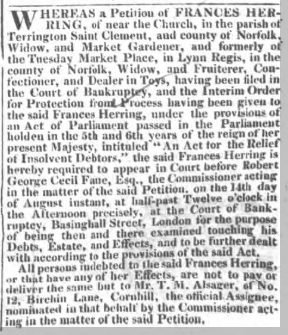

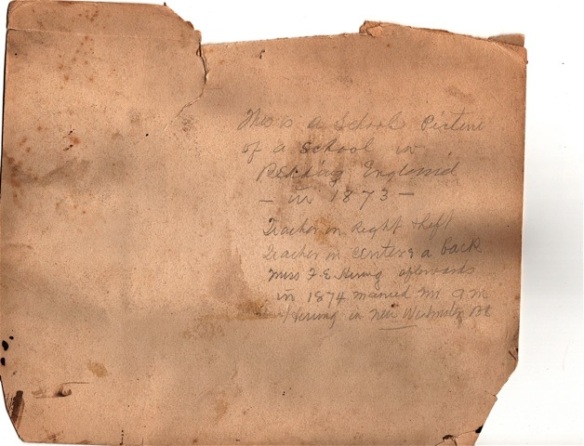

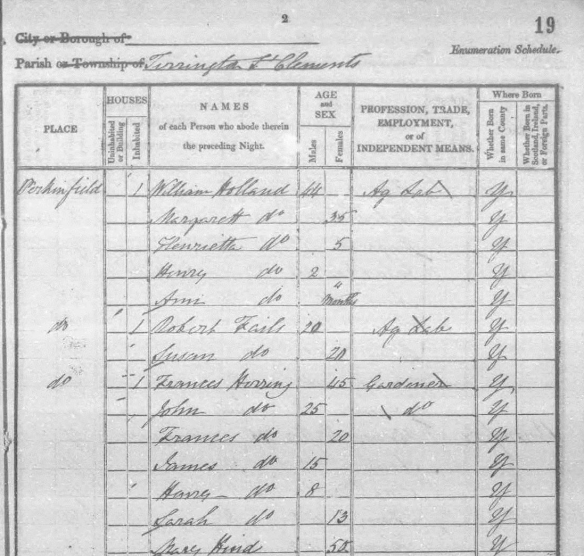

Unfortunately, this is where our official sources fail us and we are unable learn how Frances Elizabeth went from Terrington St Clement to Reading. We are enormously fortunate though, as we do have access to unofficial sources, which force us to reconsider whether or not Frances Elizabeth was writing fiction or fact.

This is particularly true of the book Ena, which seems to me to be the most autobiographical of F.E. books that I have read to date. The book is named for the protagonist Ena, a name that is formed from some of the letters of “Frances”. The book starts with the untimely death of the Ena’s father ‘John Hetherington’ no coincidence if you remember F.E.’s father’s name was John Jonathan Herring.

With opening words, we are thrown immediately into a tragic family drama,

‘Wake and come quick! Miss Ena! Miss Ena!’ called a sturdy maid-of-all-work, as she vigorously shook a little girl of nine, adding in an awe-stricken whisper, ‘you’re father’s a dyin’, wake up and come quick!’

It was a chilly morning early in May, and the child shivered as her clothes were hastily put on, and she was hurried by the maid into ‘Daddy’s’ room. He was propped up with pillows, and the grandmother, with her healthy rosy face bathed in tears, stood near him, soothing as best she could his last moments, and trying vainly to understand the dying injunctions, he strove, too late, to give.

Her mother stood at the foot of the great lumbering, handsomely carved, ‘four post’ bedstead, almost hidden by its heavy hangings of dark grey merino. She was crying weakly, quietly; hardly realising that it was the end of John, and his kindly, unselfish care of her and the little ones. But as her mother closed the eyes of the man, and the poor wife felt that all was over, she broker out hysterically, calling him to come back and not leave her to bear the burden alone. ‘How can I manage things, how can I: how can I?’ she moaned.

There was a loud wailing from a cot near, and Grandma took up a dark wiry mite of a baby girl, some two months old, and tried to make daughter take an interest in it, but to no purpose.

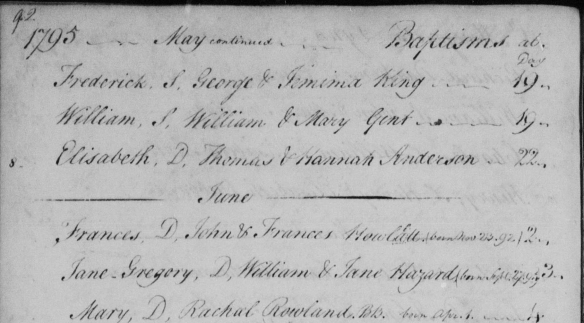

So, how does this line up? Well, John Jonathan died May 18th, 1855 in Terrington St Clement. F.E. herself was about eight years old when he father passed and her youngest sister Jane Howell Herring, born March 28, 1855 was just a little less than two months old.

We learn a bit more about John in the last lines of the first chapter,

Mr Hetherington had been in business in Granston, but his health gave way, and he was not equal to the strain it imposed upon him; so he had lately come into a few acres of land, the old homestead, and a little money, he resolved to leave the town life, and try what the country air, and out-door occupations could do for him. His wife had never liked the idea, the very name of ‘the country’ suggesting loneliness; besides, she left behind her all the friends and acquaintances of her life.

Mr Hetherington had put some sheep and lambs into the house orchard, and it was in looking after them he took a severe cold, which resulted in inflammation, and his rather sudden death.

So it sounds likely that John Jonathan came into possession of the land originally left to his mother Frances (Howlett) Herring, by her father John Howlett as described in our previous blog post The Herring Family: Back to the Beginning.

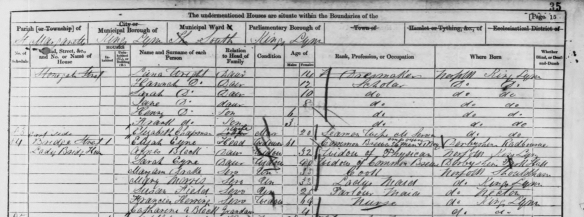

We see Frances living there in 1851 with her daughter Frances, Frances’s husband Jewson Earish and their son Rodger in the census records. The Earish Family would emigrate to the US shortly after and it is likely that Frances could not maintain the property herself, and passed it on to her eldest son, John Jonathan.

The book describes Ena’s difficult family relations. Her brother, also called John (as in real life) was their mother’s favourite. It was only for her grandmother’s interventions that Ena was educated and took her teacher training at Reading, as did F.E. By the sounds of it both the Mother and eldest son were quite spoiled, to the point where John was drinking and gambling in the novel.

But there are key points from which the novel deviates from real life. In Ena, the mother remarries and makes Ena’s home life even more difficult. In reality, however, Harriet (Clarke) Herring never remarried. Perhaps the novel was the origin of the family rumour that F.E. immigrated to British Columbia because of a falling out with her stepfather. Similarly, there is also a pathos laden scene in which her younger sister Hattie dies, which did not actually happen. The novel also ships the drunken gambler John off to Australia, but in real life it was the younger Paul Howell Herring he would live out his final days down under.

However, some of the scenes are so strange, that you get the real sense that they were based on real life events. For instance, there is a passage that describes some home renovations the father had undertaken and how he gone into town to pay the contractor ‘Reed’, but returned home without the receipt. He intended to return to collect it, but fell ill instead. After his death, Reed made a claim for £90 against the estate. As described in Ena,

Mrs Hetherington explained about her husband taking the money to him (Reed), and losing the receipt. All to no purpose, he blandly insisted upon the production of the receipt, which he knew was impossible, for he had himself picked it up from his office floor after Mr Hetherington’s departure, and as soon as he heard of his death, had put it in the fire.

Without the receipt, Reed could sue the family for payment of the debt and mother was forced to pay the funds a second time. This strange turn events, seems too detailed to be completely fictional, could it in fact have happened?

Ena is well worth the read, and an unbelievable legacy left to our family historians curious about more than names and dates and wanting to know instead about the stories that have shaped the family. We’d love to hear more from you. Have you read any of F.E.’s books. Are there parts you believe are more fact than fiction? Let us know!